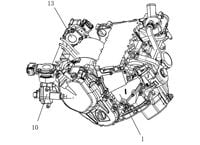

My sixth pick is the Honda RC211V, that company’s 990cc, V-Five four-stroke MotoGP bike. As the 1980s opened, the new big four-strokes had the chassis, suspension and tires they needed to bring high performance to the masses (that’s us) because the big two-stroke racebikes had forced a revolution. That new synthesis brought us Suzuki’s GSX-Rs, Kawasaki’s Ninjas and Honda’s Interceptors, all of which represented a giant step forward from the 1000cc, air-cooled four-stroke wobblers of the late 1970s.

But it’s easy to make a 100-hp, 1000cc bike smooth enough to ride; just tune the engine as if it were going in a cruiser. What happens when we go for 200 hp? Honda found out as it developed the 211V. A Honda test rider in the early going gave it a 2 out of 10 rating, saying, “The power cannot be used.”

In 2001, with the new MotoGP series less than a year away, problems persisted. “Improved throttle control is essential,” another test rider insisted. Heavy technology was deployed, but it was soon clear there wasn’t time to get automated systems right. So, the engine’s powerband was carefully tailored to what the rider could use—not driven to the limits of physics. Once smoothness was set as the goal, the new bike became quicker off corners than the previous two-stroke 500s. With velvety-smooth power, the rider could begin acceleration much earlier, and once the machine neared upright, all that displacement exerted its muscle. Smooth, usable power. Records fell right and left, and the 211’s riders dominated the sport for two solid seasons.

Since that time, competition tightened everything, forcing development of electronic torque smoothing, traction control, anti-wheelie and all the rest. But the process began with RC211V. It persuaded the engineers that the only useful power is power shaped exactly to fit what the tires can transmit.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/RZLIJNJ2IVD77CGCALO6SDZEBQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QN6WXD46FNG5LLSJWZ5EQG4ADY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ME2V7PFKK5F7LBOGFIGSNWC7GY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/NM3PTGYBLRGFJLPMKCFY6GJRFE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/XM4FNTBVW5B53GWUDMRSM5ETME.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/JG7ELFT7RVEBFMTMSJU36U4ORI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/PXXWAF26FRGVNKNPW6NWQNBTOI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZRISDVPWQZFMDJHUNAZUJWEXM4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZZHCMJA3ZNFCZF645ZSEN3NBJE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/HLN3SUOO3VGWBGG43RYVNN6A2Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CG4JZR66CJBERHQUO2A5B57QOQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3BZ5OO6MGFAP3I3MMXANK2E2UQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/EJ43BWDGNJHI3IBR7XZRUJZQ4A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OQVCJOABCFC5NBEF2KIGRCV3XA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/IGNARDBROZAHXJOWS3HJX5RFLI.jpg)