Italian cows are huge, the secret motorcycle lane down the center of Italian roads is not one-way, Hannibal driving 37 elephants through the Alps really was a pisser worthy of the history books, and relieving yourself while wearing gloves is nearly impossible.

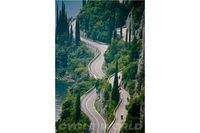

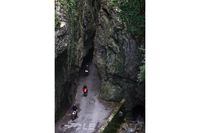

Those are things I learned while taking part in the three-day 2011 Italian Legendary Tour (ILT) hosted by Dainese AGV. This third ILT had over 60 riders, a mix of contest winners from a dozen countries, dealers, journalists, Dainese AGV personnel, tour guides and four famous world champions from four generations. The ride was from Vicenza in the east, across the Southern Alps to the original capital of a unified Italy, Torino, known as Turin to us non-Italians.

I’m unsure what the point of this event was, but I suspect it had something to do with marketing and editorial coverage. Whatever it was, the event was ambitiously over-planned, exhausting, confusing, borderline abusive and thrilling. I loved it. It was three days of the type of irresponsible behavior that’s been litigated out of existence in most countries. God bless the Italians.

I experienced the entire event in the fog of jet lag, aka sleep deprivation. I arrived in Vicenza, and after hours of sitting on a curb, attending a cookie-and-juice festival, touring a distribution center, attending a presentation about the ILT or something, taking a couple of bus rides and getting an oral history of Dainese AGV from the days of Caesar Augustus forward, I found myself at dinner seated with my riding group of journalists and World Champions Carl Fogarty and Marco Lucchinelli. Fogarty isn’t exactly Italian, but he did ride a Ducati to more than one world championship, so he is an Italian legend.

Nearly every of Fogarty’s racing stories included mention that the rider he was talking about had a faster bike than him, which he said always pissed him off. I’d wondered why, in his day, Fogarty seemed like a pissed-off racer. Mystery solved. I doubt, though, that all of his competition actually had faster bikes than him. But believing that obviously worked in his favor, so I guess he was right—right to think thoughts that pissed him off enough to win four world championships, the Isle of Man and other international races.

After speed sleeping for six hours, we were on motorcycles. I was assigned a Ducati Multistrada. We were split into eight groups of about eight riders each, designated by colored armbands and warned never to lose sight of our group leader.

Our group leader was Paulo. Paulo was sly. Paulo made a competition out of our assignment not to lose him, making it his assignment to lose us. If there was an intersection half a kilometer after Paulo passed a bus, any one of us might still be trying to learn Italian from our co-workers on a Tyrolean farm. Paulo succeeded in losing a few of us a couple of times during the first two days. After that, we rode in terror, tethered by eye to Paulo.

Adding to the difficulty of this task was that the riding groups were in concept only. While one might figure that the point of groups is for each group to ride separately, that wasn’t the case. Our group, being journalists, was always accompanied by a famous racer, whose presence inspired all group leaders to intertwine their group into ours so that every attendee could have the experience of riding with a famous racer. Riders interpreted this to mean that they needed to be as close as possible to the champion, who was always riding right next to our group leader, who we refused to let out of our sight. This resulted in the eight of us rudely jamming our way by every rider who innocently tried to rub up against a moment of fame.

On the third day, I traded my splendid Multistrada for a Diavel, which made me nervous because I doubted that this cruiserish thing could handle the pace in the switchbacks. But in this back-to-back comparison between these Ducatis, I discovered that whatever the Diavel might be when it's parked, it's a sportbike when it's in motion; it handles like a middleweight and shoots off the corners like a heavyweight.

The conflict of intermingling riding groups came to its zenith on the third day when Marco Simoncelli joined us with his girlfriend, Kate Fretti, in matching Marco helmets. On that day, there wasn't even an instant of pretense to there being eight groups. Right from the hotel steps, it was 60 bikes racing to be next to Simoncelli's bike, while he rode next to our group leader, who eight of us were racing to keep near.

And now, as I work on this story some months later, Simoncelli’s death shows the fragility of life and how precious a moment can be. My time near him has intensified my feelings of loss, his personality so lifting, his joy so engaging, his nature so easy. His passing away has hit me hard. Maybe in time I’ll be able to say more about that. For now…

Paulo also tried losing us whenever we stopped. No rider can put on gloves and helmet as fast as this man. If any of us were without our helmet and gloves in place when Paulo started putting on his, seconds later we’d be sitting on gloves, chest whipped by a flapping helmet strap, hoping for a red light and a chance to struggle with zippers, straps and Velcro. After leaving two of our group behind at one stop, Paulo later scolded them for not being part of the group; forget about the fact that he rode off and left them without a glance back.

Have you ever tried to relieve yourself while wearing gloves?

Contributing to our terror, all that we had for directions was a cartoon drawing of a squiggly road under clouds and mountains. Some villages were named on that page, but not a single intersection was shown or route number listed. All that Paulo would tell us was that we were 50 kilometers from wherever we were headed, no matter how many kilometers we’d covered since last asking him.

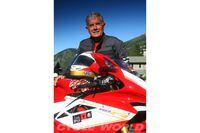

On day two of the ride, 15-time world champion Giacomo Agostini rode with us. Lucchinelli referred to Ago as Jesus, the truth of which we saw by the reaction of every Italian. Women from their 20s to 70s hugged him. Babies were shoved into his arms. And even though he's in his 70s, there's no doubt he could ride straight across Lake Como; laws of the highway, and of nature, don't apply to Ago.

While riding for these 790 kilometers through the Alps, I somehow inadvertently stayed on the happy side of ineptitude, luck and exhaustion, not once falling off a motorcycle. Though I’m happy about that, I also feel a sense of failure. I mean, this event was hosted by a premier protective-gear company, and I was wrapped in its armor from toes to nose, yet I failed to effectively test any of it.

In concept, the ILT was a prize awarded to dealers from a dozen countries and 15 lucky Dainese customers. But due to the unending sleep deprivation and the ride’s frantic pace, it was a weird endurance test that had grown men nearly crying. Pretty much all I saw were apexes and cow manure, with hints of the Alps’ grandeur in periphery. I have the vague impression that the Alps might be a nice place to visit. I only noticed lakes and cliffs and mountains when I needed to avoid crashing into them. One rider confessed to me that he twice fell asleep on his bike. By the end of the second day, I realized that my unresolved jet lag no longer mattered because even the Europeans had become so exhausted they were reduced to my semi-conscious level.

Since I don’t generally hang out with Agostini, I wanted to ask him something telling, but interviewing him struck me as idiotic. How many books have been written about him and how many interviews had he already suffered, and would suffer in these three days? What could I possibly ask that he hasn’t already been asked? “Is Sophia Loren still as hot as she looked in the Pirelli calendar of a few years past?” No, that’s crass.

So, while Ago sat resting with his new AGV signature gold, green and red helmet on his lap, I asked him the only thing I could think of that he might not have already been asked: “Ago, is that a real Agostini helmet in your lap, or is it a replica?” He said it was a replica, but I’m still pondering if he was right. I mean, if he’s Agostini, so what if he grabbed a helmet off the assembly line? If it’s on his head, it has to be the real thing. Isn’t that ever the only difference between real and replica?

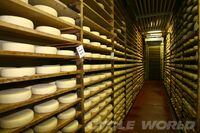

In my slumbering semi-consciousness, there were things I did glimpse that momentarily woke me like in the way a barking dog unsettles a dream. Just below the Southern Alps are fields of corn where it looks like Ohio—except, of course, for the 16th-century castle looming above the maize. When rounding a switchback, I saw a tractor pulling a narrow trailer with gated sides, and in it was a bull the size of a Dodge Power Wagon, sporting a 10-kilo nose ring in fist-sized nostrils. As we were speeding through a nameless village, a girl on a scooter passed by in the opposite direction, her shoulders leaned into the wind, her black ponytail whipping against her back, her skin soft and pure in the sun. Her image was the beginning of a movie I’ll never know the end of.

We stopped short of Turin, hooking up with a police escort for the ride into the center of the city. With Simoncelli and his girlfriend still present, it was a 60-bike urban GP without the annoyance of needing to stop at traffic lights. At the city’s center, we stopped for photos at a square, and one of our group’s members ran to relieve himself, the rest of us promising to cover for him. Suddenly, we were told to mount up. I asked a Dainese representative if we could wait a couple of minutes for our missing rider. “No,” she said, “we’re on a tight schedule.” I wondered if she remembered that part about me being a journalist. Thankfully, he came running back seconds later.

Wine for dinner? It was an accident. After dinner and a few bottles of wine were consumed at our table, I handed my keys to Paulo, asking him where the bus was picking us up. He handed the keys back to me. What the hell, when I’m with 60 other riders who’ve also imbibed unknown quantities of wine, and we’re blessed by a police escort, I’ll make an exception about wine and motorcycles.

At the hotel, I was told, “Your bus to the airport leaves at 3:30 a.m.”

I’d do it all again in a heartbeat.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/RO36KTIVYZEATJW7CCB77EQHLQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/BUIUXSLF5RFRVJ3E26VRO5V2AY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/EJJ2JBBSEZAWLFCRDALQOIBFVU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WVYKJFMINVFMFH37AE4OUEWVIM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/JJ3MC6GNDFF5ZNYD3KD3E4EY7Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/XH2ETEU4NVGDFNQO2XT2QQS5LU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/UFG652C27BDBFPK42TDAJ5CMX4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/AUE3NFVRRZDSBIDVUGIYIDQNUI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LYR62CH2WNBMHJJVXVATZHOUE4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/RBCTRGBQYBDK7A6XPG3HKPS7ZQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MQXQRYMZVBCWJIRYP3HEN3SHVE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TSPODNNEWRDSVJGUCNQTDG4ADI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X5TB7BDV4BA2RPSY54ZGK27RP4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/REUHOJXRDBGZ5IHBYZCCBCISPA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/52LGJTCKBFEHDF7S7H4CVUIMGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/YMWAIPIPSJAOXOU3QMJMGH37OM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/EJ6KZRGAYBCVXNL2PJXL37UVWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/AAN4TI76M5H5JMUVEIGASWXBDU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/P3RXD2UCPFF37CMB7CHPVKXORY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/VZEG2EJI2RDFZNHLRZMU56MD3Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GVJQO5FFOFBWNGODOBRB4FBAW4.jpg)