John Starley’s “Rover” safety bicycle of 1885 set a design course that the motorcycle of today continues to follow. Two wheels of roughly equal diameters are arranged as a pair of casters sharing a common pivot: the steering head, which is located above the front wheel. A handlebar steers the shorter front caster, which then steers the longer rear caster.

Beginning in 1895, French Marquis Jules-Albert de Dion and Georges Bouton had by 1900 built and sold 20,000 small, high-speed internal combustion engines, their concept licensed from Nicolaus Otto. What sensible person could resist attaching such an engine to a bicycle? Ever pedal up a hill and end up walking, exhausted, and pushing the bicycle?

Also natural was the bicyclist’s desire for more than one ratio between pedal crank and rear wheel: lower for climbing hills, higher for riding on the flat. William Reilly of Salford, England, patented a two-speed hub gear in 1896, and a three-speed in 1902. Most motorcycles of today have six speeds, located in the engine cases rather than in the rear wheel hub.

The position of the motorcycle’s engine was determined by experiments performed by two Russian-born Parisians, Michel and Eugène Werner. The engine position of today’s motorcycle is still the one they found best around 1898.

Many efforts to improve on this early work have been made—think of the “high-tech” decade of 1975–1985, when so many kinds of alternative steering and suspension concepts were built and tested. What was discovered was that there are many ways to make a useful motorcycle, but the great majority of today’s motorcycles are built in the simple form devised by John Starley and the Werner brothers.

At first it seemed that powerful concepts developed in Formula 1 would quickly show superiority. When they were applied to the motorcycle by a variety of ambitious engineers, the results did not immediately displace the classic form. Honda and the French Elf fuel company brought the new ideas plus serious backing to motorcycle grand prix roadracing, but they failed to show superiority. They worked, but they didn’t show useful improvement.

The result has been a new appreciation of simplicity. For example, the “feel” so important to racers seemed to be degraded by passing through the ball joints and linkages, hub pivots, and A-arms of the high-tech movement. Aha! Most motorcyclists have never raced, so “feel” is important to only a few specialists, right? So why worry? But simplicity not only performs well, it reduces parts counts and overall cost. Hard to resist—unless you just find complexity attractive for its own sake. Nothing wrong with that, provided you can afford the extra parts.

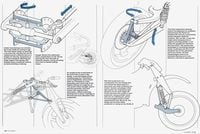

Therefore the development history of the motorcycle has focused on refinement. When the natural springiness of the bicycle’s slender fork was unequal to the road shock generated by engine power (as in “It broke”), front suspension systems came into being: Triumph’s tilting fork, Harley’s leading-link “springer,” the zillions of girder forks. The competition among these took time to resolve, but today the sliding telescopic fork is dominant, lately made more and more supple by adoption of slippery Teflon-based bushings and extremely smooth hard-coated tubes. Sensible persons, seeing that maximum bending stress on fork tubes was just below the bottom fork crown, inverted the whole apparatus, placing the stiffer, larger-diameter member at the top and the inner, sliding member at the bottom. Details, but not revolutions.

Also, important changes in motorcycle design are usually invisible. For example, the development of shock-free compression damping, which prevents your suspension from turning your bike into a jackhammer over bumps. Radial tire construction, which deploys greater footprint area to increase grip, but without increased heating. Carburetors died and fuel injection lives on, unseen inside the intake airbox. Lightweight casting methods, allowing a 30-pound weight reduction per bike (and eliminating most structural welding). Engine balance shafts are invisible inside the engine cases, reducing vibration so much that chassis and other structure can be reliably lightened.

The first Teflon-bushed fork I laid hands on was the Kayaba 36mm unit on the 1976 KR750 roadrace bike. On Erv Kanemoto’s KR Gary Nixon was able to run into the old turn 10 at Loudon, New Hampshire, on just the front wheel, his rear tire wavering, but stably, 3 to 6 inches off the pavement. That was a huge improvement over the jerky “stiction” of most forks of the time, and progress since then has been cumulative.

Chassis evolved from the single-plane bicycle design, compelled by the chain pull from the engine, tending to pull the rear wheel to the drive side. Self-steering! Chassis changes, invisible under the engine, fixed this. Each step took time; first came recognition of shortcomings. When Stan Woods on the swingarm-equipped 500 Guzzi won the Senior Isle of Man TT in 1935, the bewhiskered old-timers murmuring “nothing steers like a rigid” fell silent. The same happened in US AMA dirt track when Albert Gunter and his acolyte, Dick Mann, quietly adopted rear suspension and made it win races. They didn’t talk about it, so nobody considered it important. Whatever works soon comes to define what looks good.

The more power engines made, the more conventional chassis flexed, fatigued, and broke. “Snapped like a carrot” was the phrase applied to Norton’s 1930s single-plane chassis. The result was the boxlike “Featherbed” twin-loop tubular frame designed by the McCandless brothers and adopted on Norton’s factory GP bikes for 1950. It provided a wide base for the swingarm, which had become the dominant form of rear suspension by the 1950s. To most onlookers, it was just another chassis of bent steel tubes.

Trace the evolution of any part and you will see constant detail change, while the basic nature of the motorcycle remains that of the bicycle.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/XH2ETEU4NVGDFNQO2XT2QQS5LU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/EO5R5HI64T2USDHO3WSOVG42EM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MQXQRYMZVBCWJIRYP3HEN3SHVE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TSPODNNEWRDSVJGUCNQTDG4ADI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X5TB7BDV4BA2RPSY54ZGK27RP4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/REUHOJXRDBGZ5IHBYZCCBCISPA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/52LGJTCKBFEHDF7S7H4CVUIMGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/YMWAIPIPSJAOXOU3QMJMGH37OM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/EJ6KZRGAYBCVXNL2PJXL37UVWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/AAN4TI76M5H5JMUVEIGASWXBDU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/P3RXD2UCPFF37CMB7CHPVKXORY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/VZEG2EJI2RDFZNHLRZMU56MD3Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GVJQO5FFOFBWNGODOBRB4FBAW4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/BIVAK2SFIBDJJM25E7I5VU2FJE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CH5VX52UG5CFHOVH5A6UYEFWWA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZVGJNGZRU5C33N7KN23BBFKSC4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CZ5OM3E43ZEXJHY7LCYXCHLIKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/DF5T4K5KPZFJXFCTGPYR77PKJM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/RMCT2KVQBJHBZMRTSLOVPMOILU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/K45KB2XHQVA65DX7VN4ZSMT2BI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FNHXQQ56BRD7TO4YIJ453PNG2M.jpg)