For a company that doesn’t (yet) compete in MotoGP where aerodynamic supremacy is the difference between winning and losing, BMW’s motorcycle aero engineers have been hard at work in recent years filing flurries of patents around a variety of airflow innovations. The latest is a little different, though, as it’s intended to find a way to replicate the effect of a larger fairing without adding anything that might spoil the styling.

In the last few months alone we’ve seen patents filed by BMW showing active, movable winglets for superbikes, a passive internal ducting system to generate downforce in corners, and adaptive flaps to cover radiators and smooth airflow when less cooling is needed. Meanwhile the latest generation of S 1000 RR and M 1000 RR—fresh from delivering the brand’s first WSBK title—feature some of the largest wings we’ve yet seen on production bikes, claiming improved downforce without additional drag compared to their predecessors.

While those wings (the term “winglet” suggests a daintiness that’s lacking in the latest generation) are without doubt aggressive and effective, they demonstrate one of the clear problems with the latest generation of motorcycle aerodynamic developments: Nobody would call them pretty. That’s where BMW’s latest aerodynamic idea comes to the fore, as it aims to introduce benefits that might normally be gained from adding more external addenda to a bike, but without the visible bolt-on parts.

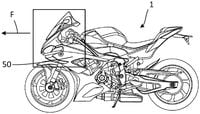

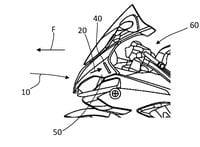

The trick is to use airflow itself to replicate the effects of bodywork. Specifically, the new patent application aims to help separate the airflow at the edges of the front fairing, just ahead of the handlebars, so it detaches from the bodywork and flows around the rider without creating excessive drag. BMW’s patent explains that the normal way to achieve this would be to add separation edges, also known as “tear-off” edges—essentially a form of lip spoiler, as often seen on the back of a car’s trunk or at the top of a tailgate—but that adding such separation edges would make the bike uglier and wider. To get the same effect without a visible protrusion, the idea is to scoop high-pressure air in through the bike’s existing nose intake and direct it through ducts inside the front fairing, so it exits from narrow slots just ahead of the rider’s hands. By making this high-pressure air exit at around 90 degrees from the surface of the bodywork, BMW’s patent explains that the effect is similar to adding a Gurney flap (the thin extension often seen on the trailing edge of race car wings that sits at 90 degrees to the main surface of the bodywork, named after US racing driver and engineer Dan Gurney who came up with the idea).

BMW’s patent application says the advantages to the idea are that the fairing doesn’t need to use unsightly add-on separation edges that might spoil the aesthetics of its design, but also that it means the fairing can be narrower, reducing the bike’s frontal area. What’s more, the document suggests that the same idea could be applied to other parts of the fairing, and that multiple intakes and outlets could be used, offering the possibility that the ducts could be adaptively opened or closed as required, altering the aerodynamic properties of the bike, for instance when cornering.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/BNSDRE4DCJE5ZPOLGPBZPOMZEI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GO6FSVIIKNBVPLSIS7IBWE7AEM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CS6TMZNTENGKFDW56HSE2HFZ2M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FUFID44YDBAM3EHF2AV5LDHLVE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QKEXZXUGVFATPE7RAT3HAHDQZ4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/T7GEMBOUDBHX7EDP2PRQ2J2XME.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4CKRUKLKZD43FDSDLZHBL7YVA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OFSXJJ5PZFEZ5D5ZPMCFVHJUMA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/N2JLNLG44VEKBMEPORRDTMX5A4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/PYWEGG6FHJD6XLPKICS7XHMMZ4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/XXFQQQ4AYJDCXDGVW3JTHAYONI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WMF36OICPZEJDPKABMHQVHXBZ4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3DJ46QYFAJA5RIJILQR2XIZXM4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4HYMMY6K4JHMNEQ56FXTGAHKG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KUENZXA3RFBIHIDGHEEVH6YNYE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/UW6THULV65E4TDI4DWLOMDR7LY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5S5CDZTZPJBHJBLHENVXEFYKG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/RWF5RV5L55DMXMWZS2D3HZRJFA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/JLDKEXSBAZGH7FAPRA5FMG4VII.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GGOH2AQRSVHY5C5JLNEVYLB5SU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TJJEHV3ATZFFXHUYZABHXKE2DI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/UH3JG2VVQFCWXKRD5AYN2XE3IE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/SQNSZQE645HWFF6YIUPSHPXESQ.jpg)