One skill that track riders sometimes put little emphasis on—and many street riders simply ignore—is trail braking, or braking while entering a corner with the bike leaned over. For track riders, trail braking is a key to not only faster lap times, but also to creating passing opportunities in a race. And street riders would do well to at least become familiar with and practice trail braking on a regular basis, as it will come in handy when it comes time to avoid an object or if you enter a corner too hot.

Trail braking, when performed properly, also offers advantages in terms of your bike’s geometry and handling. Under braking, weight transfer compresses the front suspension, decreasing rake and trail and improving steering accordingly. If you can keep the front suspension compressed while turning, you will benefit from the changed geometry. Cornering forces will eventually compress the suspension anyway, and if you can keep the front end consistently loaded from the beginning of the braking zone to the apex of the corner, the suspension will remain at a consistent travel the entire time, giving a smooth corner entry.

The danger is, of course, that combining braking and cornering forces during trail braking will overload the front tire and lead to a lowside. Tires are capable of a given maximum load, regardless of direction; it’s how you divide that load between braking and cornering that’s important. Cornering load is usually expressed in terms of lateral acceleration, or lateral G, while braking is expressed as longitudinal acceleration—to simplify things we usually refer to it as braking G. A typical maximum load for a street tire is about 1 G; you can brake at 1 G or corner at 1 G, but not both at the same time. As you turn into the corner and add lateral G, you must decrease braking G accordingly.

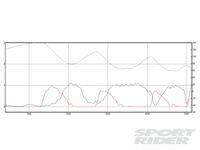

The attached data charts show some data traces for two riders at Thunderhill Raceway Park in California. Figure 1 shows speed (grey), braking G (red) and lateral G (blue) for an expert-level rider in the first three turns of the track. In turn 1, braking G peaks at about the 1500-foot mark and then gradually decreases as the rider enters the turn. At the same time, lateral G gradually increases as cornering forces take over. Note the steady change in each trace as it ramps up or tapers off, indicating smooth application and release of the brakes, and a smooth entry into the corner. At a certain point the braking G and lateral G traces cross, and this point gives a good indicator of performance. In the first turn, the traces cross at about 1800 feet, with .7 G for both braking G and lateral G. This data represents a stock bike on stock tires. Note the typical maximum braking G and lateral G maximum values of approximately 1 G, typical values for standard sport tires. A crossover point of .7 G indicates very aggressive trail braking for that combination. Modified bikes on stickier tires would show higher numbers and more trail braking.

Further into the lap, similar crossover points show about the same level of trail braking entering turn 2 at 3000 feet, and turn 3 and 4400 feet. Again, note the expert rider’s consistency in not only the peak values but also the rate at which the traces ramp up to maximum or trail down to zero. For the math types, the forces add using vector sums, and the vector sum ideally remains at a constant value close to maximum through the entire corner. If maximum lateral G and maximum braking G are 1 G for a particular data set, we would expect to see a crossover point of .7 G under trail braking. The vector sum at that crossover is 1 G total, almost the same value as the rider manages for each trace separately; this data shows the rider using trail braking to maximum effect. If the load on the front end remains constant—the rider can keep a constant vector sum of lateral G and braking G—the suspension will be at a consistent travel through the whole sequence, giving a smooth corner entry.

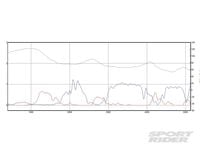

Compare that data with similar data for a slower rider in the same three corners. Obviously, speed is lower, as is braking force. It may seem surprising to see lateral G almost identical for both riders, but this is often the case—many beginning riders will carry almost too much corner speed, especially compared to their entry and exit speeds. What we are interested in here is that the novice rider combines very little braking and cornering forces—no trail braking—and if there is any crossover point it is at a very low value. Note also the very different shape of each section of the traces, indicating a lack of consistency in braking and corner entry.

Trail braking is not a skill that you can expect to master in a short period of time; indeed, even experienced club racers can have difficulty managing the braking and turning combinations. The first aspect to work on is the smooth release of the brakes, and you can practice this in a straight line. Apply the brakes as normal, but instead of quickly releasing the brakes when you reach your desired speed, slowly release them. Note how your bike’s suspension may have reacted differently and how your speed and distance were affected.

Now to add some turning. This is best practiced on the track in a simple corner with plenty of runoff, but you can also experiment in a clean and dry parking lot. As you are releasing the brakes, lightly apply some force to the inside bar to initiate a turn and continue to release the brakes. Try to combine the braking and turning so that your front suspension stays compressed as you turn, rather than extending as you release the brakes and then compressing again as you enter the corner.

Continue experimenting, braking later and turning earlier in the sequence so that you are harder on the brakes while turning. Ideally, you want to time the release of the brakes so that you are completely finished braking just as you reach maximum lean, slightly before the apex of the turn. You will definitely not get to that point without a lot of practice; take your time and ensure that you keep that smooth transition between braking and cornering.

It's important to know that not only rider skill plays a part in trail braking; tires—the type and their wear—are very important. While the pictures included here show some pretty aggressive trail braking, you shouldn't expect similar performance from your standard motorcycle on sport-touring tires. Still, the data here gives an idea of what is possible even with a box-stock motorcycle and basic sporting tires. No matter what you ride, with practice you will have smooth corner entries and be able to brake later into corners. This will lead to better lap times for track riders, and street riders will be better prepared for an unexpected surprise on the road. SR

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/AUE3NFVRRZDSBIDVUGIYIDQNUI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LYR62CH2WNBMHJJVXVATZHOUE4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/RBCTRGBQYBDK7A6XPG3HKPS7ZQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MQXQRYMZVBCWJIRYP3HEN3SHVE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TSPODNNEWRDSVJGUCNQTDG4ADI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X5TB7BDV4BA2RPSY54ZGK27RP4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/REUHOJXRDBGZ5IHBYZCCBCISPA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/52LGJTCKBFEHDF7S7H4CVUIMGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/YMWAIPIPSJAOXOU3QMJMGH37OM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/EJ6KZRGAYBCVXNL2PJXL37UVWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/AAN4TI76M5H5JMUVEIGASWXBDU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/P3RXD2UCPFF37CMB7CHPVKXORY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/VZEG2EJI2RDFZNHLRZMU56MD3Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GVJQO5FFOFBWNGODOBRB4FBAW4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/BIVAK2SFIBDJJM25E7I5VU2FJE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CH5VX52UG5CFHOVH5A6UYEFWWA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZVGJNGZRU5C33N7KN23BBFKSC4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CZ5OM3E43ZEXJHY7LCYXCHLIKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/DF5T4K5KPZFJXFCTGPYR77PKJM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/RMCT2KVQBJHBZMRTSLOVPMOILU.jpg)