This article was originally published in the April 1999 issue of Sport Rider.

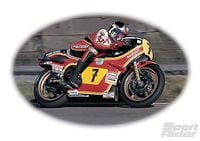

I can remember the moment like it was yesterday. Back when I was 18 years old, I was watching an episode of "Wide World of Sports" which happened to be covering the British GP held at the Silverstone racing circuit. After trading the lead with Barry Sheene in an incredible duel the entire race, Kenny Roberts made a banzai move right at the apex of the last corner and managed to hold off Sheene by a half-bike length at the finish. It was the most exciting race I'd ever seen and it galvanized my interest in roadracing. Prior to that race I was a motocross fan, but from that point onward all I could think of was Grand Prix roadracing.

Later, when I would lie in bed and stare at the posters of Roberts, Spencer, Mamola, et al., I often wondered what it was like to ride those bikes. I’d heard stories of wicked powerbands that threatened to spit you off, along with chassis and tire setups that could barely deal with that power. How difficult were those GP racebikes to ride—were they really that cantankerous?

Twenty years later, as a magazine editor, I was still left wondering. Oh, I'd had the fantastic opportunity to throw a leg over cutting-edge GP machinery—like Mick Doohan's NSR500, as well as Tadayuki Okada's works NSR500V back in '97. But what about the glory years just before the advent of twin-spar aluminum chassis, carbon brakes and radial tires?

Little did I know that the chance to find out would come when I received a phone call from Cliff Tolley, a former racer now residing in Los Angeles. “How would you like to ride a couple of classic GP racebikes?” asked Tolley. “We’ve got a Honda RS500 triple, a Suzuki RG500, plus an RG700B.” An RG700B? “Yeah, Suzuki made a few of them in ’78 and ’79 for the [Transatlantic] Match races and Formula 750 class. They’re basically a big-bore RG500 square-four. We’ll be bringin’ them out to Willow to run them in, since we’ve just gone through the engines to make sure everything was OK. Care to try ’em out?”

Whoa—talk about a chance to ride some real history. The RS500 was a for-sale-to-privateer-racers replica of the V-three, two-stroke NS500 works bike that carried Freddie Spencer to his first world championship in 1983. The RG500 was a square-four (basically two parallel twins running in tandem), two-stroke racer that carried Barry Sheene to two world titles in ’76 and ’77. In later incarnations it also assisted Marco Luchinelli and Franco Uncini in their successful title chases in ’81 and ’82, respectively. But I knew very little about the RG700B, until I arrived at Willow Springs.

This '79 RG700B is owned by Tim Saunders, a work partner and friend of Tolley's. Originally ridden by Virginio Ferrarri (a perennial GP contender in the late '70s for Suzuki) the bike had somehow escaped the crusher that normally awaits factory racebikes after their one- or two-season life span is used up. When Saunders took delivery of the bike it was in fairly good condition, externally. But upon checking the engine he discovered someone had put antifreeze in it. Unfortunately the RGs have magnesium crankcases, and antifreeze chemicals have a corrosive effect on the lightweight metal. The cases were essentially junk and one of the crankshafts was ruined.

Luckily, Saunders was friends with Roberto Gallina, an Italian who was Ferrarri’s GP team manager during the 1980s. It turned out Gallina had a ton of spare parts collecting dust at his shop in Italy. When the RG was shipped over, Gallina’s mechanics immediately assisted in restoring it to its former glory—within a day, the bike was running.

Technically known as the XR23B, the 652cc square-four was built during an era when the FIM Grand Prix had many more classes than the current 125/250/500 divisions. One of these former divisions was the Formula 750 class, where multicylinder, high-horsepower two-strokes did battle. Although the RG700B wasn’t specifically built for this class (according to the book Team Suzuki by Ray Battersby, an incredibly definitive analysis and chronicle of Suzuki’s early GP days), many of these bikes were raced in this division as well as the famous Transatlantic Match races, where teams from the United States and England raced against each other at several British tracks.

The RG700B is basically the same format as its smaller RG sibling, using rotary-valve induction for its four separate Mikuni, funnel-type carbs. (The 700 uses 36mm carbs vs. the 500’s 34mm.) The frame is a tubular, mild-steel cradle, but the swingarm is a braced, box-section aluminum piece. The antidive-mechanism-equipped Kayaba fork (remember those?) uses nitrogen-pressurized tubes that measure a mere 37mm, offering 5.1 inches of travel. Rear-suspension units on the bike I rode were of unknown origin, although the originals were equipped with twin Kayaba “Golden Shocks,” which were pneumatically sprung, cut-from-billet-aluminum pieces that offered adjustable spring rates and rebound damping. The cast-magnesium rims measure a spindly 2.50 x 18 inches in front and 4.00 x 18 inches out back. But you must remember this was before the advent of radial tires, which require wide rim sizes.

Claimed peak power for the RG700B is 138 horsepower (the prototype was reportedly too powerful, resulting in the RG being “detuned” to 138!), and after hanging on to the thing for more than a dozen laps, I wouldn’t dispute that figure. Rotary-valve induction motors have a reputation for snappy powerbands, and the RG700 is no exception. Things are pretty dead below 5000 rpm, with the engine sputtering in protest. But once the tach rises above 7000 rpm, look out—the engine note suddenly clears out into a warbling shriek, and the big Suzuki literally bolts forward as if you’ve hit a nitrous button. With only 299 pounds to propel, acceleration is heart-attack serious until the party winds down at 10,800 rpm.

The riding quarters were pretty cramped (even for a skinny editor). The ergos for this bike were obviously tailored to Ferrarri’s diminutive build, and I found it difficult to move around. Steering manners were on the quick side, requiring little effort to initiate turns. A good thing, since using any body movement for assistance was pretty much ruled out. If you were out of the powerband, vibration was fairly intense; but once on the pipe, things smoothed out considerably. And with so little weight to slow, braking power was very good, albeit a bit numb.

The history of ownership of the RG500 is unknown. It’s a 1975 model, which means its level of development was four years earlier than the 700, and its internal engine configuration is slightly different. The ’75 version was more oversquare than the last-generation RG, sporting a 56 x 50.5mm bore/stroke (vs. the ’76-and-later models’ 54 x 54mm arrangement). This translates into a bike that is quite a bit revvier than the 700, with a crisper throttle response to match. It was much peakier, too. There’s nobody home below 8000 rpm but thankfully the powerband hit wasn’t as vicious. From there, the square-four would wail up to 11,000 rpm, where its 100-horsepower rush would trail off.

Although the claimed dry weight of 298 pounds for the 500 is only one pound less than the 700, the 500 felt far more nimble through the corners. Chassis and suspension componentry is essentially similar to the 700. Flicking the bike from side to side was much easier (although roomier rider accommodations probably helped), and the bike felt a bit lighter and snappier. Braking action from the unique “plasma-sprayed” aluminum discs was quite good.

Unfortunately, a cooling problem cut short the festivities on the RG500 after a handful of laps. Despite repeated attempts to diagnose it the dilemma persisted, prompting us to park the Suzuki before any damage occurred.

Which leaves us with the Honda RS500, and an interesting tale concerning it and the RG500. Saunders happened to be perusing The Los Angeles Times classified section one day, when he came upon an ad that read, in part: "1983 Honda 500 Grand Prix racebike, three-cylinder, same as Freddie Spencer's championship machine, excellent condition—serious inquiries only." Figuring that it was some bonehead who didn't know what he was talking about, Saunders decided to call him anyway just out of curiosity. When the person selling the bike started describing the machine, however, it became apparent that this might be the real thing. So Saunders and Tolley quickly made the trip down to, of all places, Beverly Hills.

“The RS was sitting right there in the gentleman’s office,” recalled Saunders, “and the fellow turned out to be quite knowledgeable about bikes. He was an interesting character.” What was even more interesting was the gentleman’s collection of racebikes. “He said he had some other bikes in his garage, so he led us back behind his place. When he opened the door, we couldn’t believe it,” said Tolley. There, inside a dank, musty garage, underneath a few tarps with mounds of junk piled on top, were dozens of classic racebikes. Although dusty from years of storage, many were in near-original condition. “It was incredible,” said Tolley. “Some of them had fairing parts missing, and many were getting rust on them from the moist air. But a few, like the RG, were totally original.” Tolley not only bought the RG500, he also scooped up a ’74 TZ700, complete with original spoked rims. A British friend of Saunders bought the RS.

Although primarily meant for privateer GP racers, quite a few of the Honda RS500s made their way to the States from '84–'86, ending up in the hands of notable American pilots—like Wayne Rainey, Randy Renfrow, Mike Baldwin, Rich Schlacter, et al.—and competing in the AMA's now-defunct Formula One class (where two-strokes up to 750cc did battle with the 1000cc Superbikes of that period). Based closely on Freddie Spencer's '83 title-winning works bike, the RS500s were a step above most of the current two-strokes available at the time. Sporting a reed valve–induction, V-three powerplant producing 120 horsepower, the RS also came with a square-tube, aluminum frame and top-shelf suspension components.

My first impression of the RS was how light it feels; bump-starting the RS felt like pushing a bicycle compared with the other two. The Honda felt low and nimble—even compared with modern-day GP machinery—and carburetion was very crisp from 3500 rpm up. In fact, I was amazed at the torquiness of the RS motor. Pulling the tall first gear from a stop took little effort and there was plenty of acceleration on tap from 5000 rpm to 8000 rpm. If only Honda could turn this into a streetbike….

But the upper rev range and quicker pace is where the RS shines. Although big speed comes into play at 8000 rpm, the burst of power is easier to live with than the rotary-valve powerplants. Acceleration continues to build exponentially up to 11,000 rpm, and the excellent gearbox made keeping things on the boil ridiculously easy. Handling and steering manners were quick yet absolutely dead neutral, in everything from medium to blood-in-the-eye paces. Nothing in Willow’s pavement repertoire could upset the chassis. Railing through Willow’s ultrafast turn eight required minimal steering inputs to stay on line. And with only 275 pounds of mass being slowed by dual 295mm discs, stopping power was phenomenal with excellent fuel and power permitting seriously deep corner entries.

I began to see why Spencer’s more agile three-cylinder used to give Roberts fits throughout the 1983 season.

In an age when 190-horsepower motors and 200-mph speeds are becoming buzz words in Grand Prix racing, it’s easy to forget the era when GP motorcycles were just beginning to reach those thresholds where engine and tire performance were making that big leap forward. When many people think of classic GP machinery, they don’t immediately think of bikes that Mamola, Roberts and Spencer made famous. But if more people like Saunders and Tolley surface, that could change. I thank them for giving me a chance to experience this classic period of Grand Prix history.

Special thanks to Don Morley for the historic race photography.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/AUE3NFVRRZDSBIDVUGIYIDQNUI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/LYR62CH2WNBMHJJVXVATZHOUE4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/RBCTRGBQYBDK7A6XPG3HKPS7ZQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/MQXQRYMZVBCWJIRYP3HEN3SHVE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/TSPODNNEWRDSVJGUCNQTDG4ADI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/X5TB7BDV4BA2RPSY54ZGK27RP4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/REUHOJXRDBGZ5IHBYZCCBCISPA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/52LGJTCKBFEHDF7S7H4CVUIMGM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/YMWAIPIPSJAOXOU3QMJMGH37OM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/EJ6KZRGAYBCVXNL2PJXL37UVWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/AAN4TI76M5H5JMUVEIGASWXBDU.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/P3RXD2UCPFF37CMB7CHPVKXORY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/VZEG2EJI2RDFZNHLRZMU56MD3Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GVJQO5FFOFBWNGODOBRB4FBAW4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/BIVAK2SFIBDJJM25E7I5VU2FJE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CH5VX52UG5CFHOVH5A6UYEFWWA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/ZVGJNGZRU5C33N7KN23BBFKSC4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CZ5OM3E43ZEXJHY7LCYXCHLIKI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/DF5T4K5KPZFJXFCTGPYR77PKJM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/RMCT2KVQBJHBZMRTSLOVPMOILU.jpg)