We’ve all been thrilled by Volker Rauch’s dramatic midcorner photo of Mike Hailwood on the legendary Honda 250cc six at Clermont-Ferrand in 1967. It is therefore a privilege for me to dig out facts and relevant details relating to Cycle World’s trove of other Rauch photos, beginning in 1955 and continuing through the rise, dominance, and, after 1967, retirement of the classic Japanese Grand Prix teams.

There is for me wonderful incongruity in these other-worldly sharp black-and-white images of motorcycles and mechanics working on the ground in wooded paddocks. This was far indeed from today’s high-security “pit boxes,” lined and lighted for the event with theatrical flats carrying the corporate graphics that will be transmitted through every photographer’s lens.

When the big money comes into a sport, something is gained and something is lost.

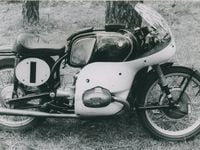

This was during BMW’s romantic involvement with the Earles long leading-link fork, whose extra mass projecting to the rear caused a slow pendulum-like wallow in long corners. BMW wasn’t the only one giving it a try. Looks like Girling units at the rear.

Note that final-drive torque reaction is not fed into the swingarm but into the link you see below it. This prevented the comical “pinion climb” that could result from rolling throttle on and off on production bikes. As you opened the throttle, rear suspension extended as the drive pinion “climbed” the axle gear. When you closed it, the rear of the bike sank. But not on this racing model. Years later, Dr. John Wittner would do the same for the shaft-drive Moto Guzzi in AMA Battle of the Twins racing.

What is that lump above the valve cover? That conceals the bevel gears driving this engine’s overhead cams. Built-for-racing, Rennsport engines like this one would win 15 consecutive sidecar world championships, 1954–’67, then five more in the years before two-stroke domination began in ’75.

Limited PR resources? This bike is posed for the photo by leaning it against a tree. In roughly the same period, Formula 1 cars were chugged through public streets to reach the starting grid at Belgium’s super-fast Spa circuit. TV had not yet turned sport into spectacle.Volker Rauch

The “two-stroke squeeze” that would by 1975 push four-strokes out of every GP class including sidecars began in the smallest class first. It pitted the ultra revs of Honda’s four-strokes against the rising combustion pressure of the two-strokes. There was no doubt of the outcome. Despite Mike Hailwood’s sensational 1966–’67 wins on the 250cc six over Phil Read on the Yamaha RD05 square-four, Honda knew that even a water-cooled V-8 turning 20,000 rpm might not be enough.

Volker Rauch

Why didn’t this begin the two-stroke revolution? Standing in the way of the 350cc DKW triple was Moto Guzzi’s four-stroke 350, a light, handy, and fast-accelerating single making up to 38 wide-range hp. As DKW riders strove to balance outcomes on narrow two-stroke power, the Guzzi men pulled away to five consecutive 350cc championships.

The name of the technician fondly gazing at this 125cc creation is unknown to us, but his obvious feelings are familiar.

Over in East Germany, MZ’s Walter Kaaden had that company’s 125cc race engine making 16.5 hp at 9,200 rpm. Two more years of development would push its little cylinder past 20 hp and the revolution was on. Meanwhile, DKW succumbed to socioeconomic forces pushing consumers away from bikes and into the affordable small economy cars that had finally been tooled for production.Volker Rauch

Sign up here to receive our newsletters. Get the latest in motorcycle reviews, tests, and industry news, subscribe here for our YouTube channel.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/R26K447HPJFXNL7HDNAIY4VOI4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U3S3JPJT5REW7NTPZMUP2FZY3A.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WPQ2LXEKPVFZRF2CZLPSDOMVAI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/BNSDRE4DCJE5ZPOLGPBZPOMZEI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GO6FSVIIKNBVPLSIS7IBWE7AEM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/CS6TMZNTENGKFDW56HSE2HFZ2M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/FUFID44YDBAM3EHF2AV5LDHLVE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/QKEXZXUGVFATPE7RAT3HAHDQZ4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/T7GEMBOUDBHX7EDP2PRQ2J2XME.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/U4CKRUKLKZD43FDSDLZHBL7YVA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/OFSXJJ5PZFEZ5D5ZPMCFVHJUMA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/N2JLNLG44VEKBMEPORRDTMX5A4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/PYWEGG6FHJD6XLPKICS7XHMMZ4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/XXFQQQ4AYJDCXDGVW3JTHAYONI.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/WMF36OICPZEJDPKABMHQVHXBZ4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/3DJ46QYFAJA5RIJILQR2XIZXM4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/4HYMMY6K4JHMNEQ56FXTGAHKG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/KUENZXA3RFBIHIDGHEEVH6YNYE.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/UW6THULV65E4TDI4DWLOMDR7LY.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/5S5CDZTZPJBHJBLHENVXEFYKG4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/RWF5RV5L55DMXMWZS2D3HZRJFA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/JLDKEXSBAZGH7FAPRA5FMG4VII.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/octane/GGOH2AQRSVHY5C5JLNEVYLB5SU.jpg)